You are here: Foswiki>Main Web>YearIndex>WelcometoUS (06 Jul 2006, GordonHarper)Edit Attach

A Note From John Burbidge

It is the 4th of July, 2006, America's Independence Day. I have now lived in this country almost as long as I lived in Australia, where I grew up. A few months ago, an e-mail from a friend triggered my memory of my first arrival on these shores 35 years ago. I have come and gone many times since, but this entry is one I have never forgotten. Over the years, I have recounted the tale in bits and pieces and often intended to write it down, mostly for my sake but also for any amusement and interest it might bring to others as well. I have now done so, and would like to share it with you. It is not a finely polished piece of writing, but simply a recollection of an important stepping stone in my life. Please accept it as a gift. May it trigger other memories for you. Have a nice day ... as they say in America. -- John BurbidgeWelcome to the United States of America!

Arriving in a new country for the first time is always intimidating, no matter what your expectations. Different styles, different accents, different smells all converge to give you the unnerving feeling that you are the outsider entering their territory on their terms. First impressions do count for something, although being too hasty to draw conclusions can sometimes be a hindrance. At last count, I had visited 34 countries and only in a handful of those was I relaxed at the point of entry, and that was probably because I’d had one too many glasses of wine on the journey. Some entries have been easier than others and some have faded from memory altogether. Others have not — Lagos, Bombay and Livingstone (Zambia) among them. But one stands out above all others. My first trip abroad was to the United States in October 1971. I had just celebrated my 22nd birthday a few weeks before and decided to take a quantum leap in my life, from sleepy, suburban Perth on Australia’s southwest coast to the ghetto—then a 99% black ghetto—on Chicago’s Westside. It would be hard to imagine two places more contrasting but I was young, naïve, and ready to take on the world, albeit secretly scared to death at what I was getting into. Just before my departure, a trusted friend and colleague who had made this journey before me pulled me aside and uttered a few words of wisdom in my ear. “Whatever you do, John, while you are in the US, don’t be defensive about Australia. America can be a bit overwhelming and some Australians overreact. Just be who you are, take things in your stride, and you’ll be fine.” That, along with the $50 bill my father gave me as parting gift just before I boarded my plane at Perth airport, were the two most valuable things I took with me.- The Author At the Time of This Story:

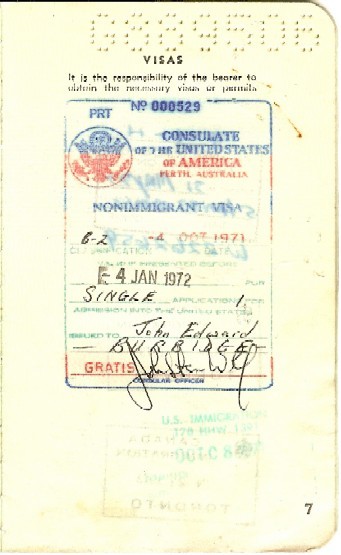

Flying to Chicago from Perth was no simple affair thirty-five years ago. It involved stops in Sydney, Fiji, Honolulu, San Francisco and New York, before doubling back to Chicago. I don’t remember the total flying hours but I left Perth on a Thursday night after working late at the office, spent a day in Sydney where I reduced my luggage from two cases to one (never to see the other again), crossed the international date line, and arrived in Chicago on a Saturday afternoon. Being a raw recruit to international travel, I lapped up every perk and privilege Qantas offered on its trans-Pacific route. Every movie they screened, I watched religiously; every glass of premium Australian wine they offered, I gulped down; every lavish meal they served, I ate every last crumb. By the time the special champagne-and-lobster breakfast rolled around between Honolulu and San Francisco, I was beginning to feel significantly heavier than when I left Perth. My body rhythms were shot and my digestive system didn’t know what had hit it. But I’d been living an extremely frugal lifestyle for the last eight months and I felt I owed it to myself to make up for lost time. My first taste of the USofA was Hawaii. After flying for hours through pitch darkness across the equator, it was jarring to look out the window and see a blaze of lights along Waikiki and Diamond Head, like a brilliant constellation of stars in the midst of one long black hole. As the captain announced preparations for landing, my stomach started to squirm. This was it. Not quite the real it, but “it” nevertheless. Although I’d lived and worked with Americans in Australia, I now was about to meet them on their home turf. I had my story ready: I was coming to the United States to do a six-month training program, after which I would be returning to Australia. I’d rehearsed it dozens of times and I had my coveted B-2 visa, which I’d secured three days before leaving Perth. I also had a letter of invitation from the Ecumenical Institute in Chicago, just in case I needed to prove the veracity of my claims. As we touched down at Honolulu, I took a deep breath and tried to calm myself. Something told me it was not going to be easy. Everyone had to leave the plane and be processed through immigration, so at least I had the consolation of being one of a crowd submitting to the same fate, as we filed down the stairs into the balmy tropical night. This was America, the country so many people yearned to visit or emigrate to, the land of dreams and possibility. But it was 1971. It was also the land of the civil rights movement, of political assassinations, of the Muslim Brotherhood, of the Black Panthers, of the Kent State University massacre, and of the Vietnam War that Australia had supported and against which I had openly protested, causing a deep rift in my family. Little wonder I had mixed feelings as I walked across the tarmac and entered one of the wide, low coaches that ferried us to the immigration building. Although I was in my early twenties, I looked, as one of my friends recently reminded me, all of sixteen. Before leaving Perth, I had worked for a short time as a probation and parole officer. It was a job I was totally unprepared for and completely out of my depth in, but it was a job, and the only one I could find after months of walking the streets of Perth with my precious B.A. Honours degree with a major in anthropology. I remember the stares of disbelief on the faces of clients and family members when, on visiting nights at my office, I would enter the waiting room and call out the name of the next person on my list. They assumed I was some flunkey who had been delegated to bring them to the real probation officer. Their shocked realization that I was it was devastating to my self-esteem. Somehow, I managed to live with it for eight months. But on this October evening, my boyish persona may have been an advantage. I’m not sure I could say the same for my orangey-brown woollen suit with flared pants and my turquoise floral shirt with matching tie that made me look like a walking neon sign. This outfit, which my mother had so generously given me as a birthday gift, was pretty cutting edge for its time, at least in tame old Perth. Even if I was a quivering mass of jello inside, I could give the impression that I was something not to be taken lightly by my state-of-the-art wardrobe. Besides, the suit took up so much room in my one case I had little choice but to wear it. As I stood at the yellow line waiting my turn to present my credentials to the official representative of the United States of America, I could feel the sweat trickling down my armpits. I looked at the overweight, middle-aged man behind the counter and tried to size him up. What was he like? Did he have a wife, two kids and a dog? Did he ever travel to other countries and have to go through this ordeal? What questions would he ask me? Would my propensity to stutter under certain stressful situations rise to the surface? The questions kept coming. Suddenly, the woman before me at the counter picked up her bag and moved on. The officer never bothered to look at me as he uttered a long, almost bored “n-e-x-t”. I strode up to the counter and pushed my shining new passport and immigration card through the gap under the glass. He fingered the passport and flicked it open to the page with the visa. He stared at it for what seemed an interminable length of time, then glanced at me, presumably to check the photograph with my face. His glance quickly solidified into a stern, uncompromising stare. “What’s your purpose in coming to the United States?” he drawled. “I, I, I’m coming for an international training program,” I stammered. “What kind of training?” “Cultural studies.” “What organization is this with?” “The E-e-e-cumencial Institute.” “Where is this institute?” “Chicago.” “How long is the course?” “Six months.” I suddenly remembered the letter of invitation from the Institute. Damn! I had left it on the plane. How could I have been so bloody stupid? “This isn’t the right kind of visa for a six-month training program. It’s only valid for three months,” the officer spat out. I nearly melted on the spot. My armpits were now like the Mississippi in flood. I had to do something. In the game we were playing it was becoming clear that I was on the losing side. “The US Consulate in Perth gave me this visa for the training program. And I have a letter from the Institute but I left it on the plane, sir.” I decided to add the “sir”—most unAustralian but a tactic I’d picked up from watching too many American television shows—in the vain hope that it might improve my position, which appeared to be getting weaker with every word I uttered. Instead, it only seemed to make matters worse. The officer’s tone changed from objective inquirer to irritated lecturer. “I’ll have you know, young man, that I decide who enters the United States, not some consular officer.” Oh my god! I began to visualize myself being led handcuffed to the next Qantas plane back to Sydney, and having to explain to everyone that I had been denied entry into the US. While I stood petrified contemplating my fate, the officer turned aside and grabbed a piece of paper from a file and slid it through the opening. “I’ll let you through this time but when you get to Chicago, you’ll need to take this to the INS office and get another three-month entry permit.” He picked up his rubber stamp, belted it down on the page underneath the visa, and shoved my passport back with the same kind of indifference with which he had greeted me. I uttered a huge sigh of relief.

- Visa With Chops:

“Thank you … sir,” I replied meekly, and beat a hasty retreat to the door marked Transit Lounge. I had cleared the first hurdle, but it had taken some doing. I had now officially arrived in America. If this was the kind of reception you could expect, I wasn’t sure I wanted to stay. But I had told my parents, friends and colleagues I was going on a six-month training program and would return at the end of that time. Much against their better judgment, my parents had generously provided my fare, having promised equality with my sister to whom they had given the same amount of money several years before when she took off for distant shores, never to return permanently to Australia again. Little did I know that I was about to follow in her footsteps. During the hour I had before reboarding my flight to San Francisco, I had one priority. Although I had advised the Institute’s office in San Francisco by mail of my arrival, I was not sure they would have received the letter, so I decided to try sending a telegram as well. In order to do this, I first had to change the precious AUS$50 bill my father had given me. It was the only cash I had. Fortunately, in these days, the exchange rate was the reverse of what it is today and I received more US dollars for my Australian ones. However, when I found how much a simple telegram cost to San Francisco, I nearly decided to abort the idea. But since I had a six-hour stopover in this legendary city, I wanted to make the most of it and went ahead and sent the telegram. Besides, I could do with a slightly warmer welcome, once I hit the mainland. Knowing someone would be there to meet me helped me regain some of my lost composure. Little did I imagine the reception I would receive. * * * On 25th October 1971, the United Nations voted to accept People’s Republic of China in place of Taiwan. At last, this global forum had acknowledged the presence of the world’s largest country. Its Communist government, under the leadership of Mao Tse Tung, had come to power in October 1949, two weeks after I was born. How odd, I thought. It was as though China and I had grown up together, albeit worlds apart. It was finally making its debut on the world stage, just as I was launching mine. Two of a kind, so to speak. It would be several more months before President Nixon would make his historic trip to China, but in the meantime, another prominent American had upstaged him. His name was Huey Newton, the 29 year-old African-American co-founder and leader of the Black Panther Party. The party had an international perspective and a belief in worldwide revolution. Imagine their delight when they received an official invitation from the People’s Republic for Huey Newton to visit. His brief stay in China gave some relief from the daily outpouring of news stories from the now disastrous Vietnam War. His arrival back in the US was eagerly awaited by reporters, so a press conference was arranged at San Francisco airport on his return. Since there were no direct flights between China and the US mainland he had to fly via Hawaii, where apparently he had joined our Qantas flight. I knew nothing of all this when I stepped outside the cabin door and set foot on the jetway. I was just relieved to have finally made it to the western shores of America, after slogging it out for four five-hour stints in the air, even though there were still another two to go. At least I had six hours on the ground and was determined to make the most of it. The key would be finding the person whom I prayed had come to meet me among the multitudes who had gathered to greet this flight. To enable this person to identify me, I had carefully pinned a thumbnail-size wedge blade, the Institute’s identifying symbol, on my broad lapel. Why I expected anyone could see this from several feet away I can’t imagine. But, as I soon discovered, even if I had carried a six-foot wedge-blade it probably wouldn’t have helped. Before deplaning, the captain had announced that all passengers would be taken to a hotel for the duration of the layover in San Francisco. When I heard this, my heart sank. The way it was announced seemed like an order, not an option. How could I explain that I was being met and wished to make other use of my six hours? Before I could think of the best way to handle this, we were ushered out of the cabin and into the terminal. After the lengthy flights and my unsettling experience in Hawaii, I was not at my peak. I was certainly not ready for what I encountered. As I entered the airport lounge, it was like disappearing into a tunnel. On either side of me, were black men and women, most extremely large black men and women, all dressed in black, some with wild afro hairstyles, lined up with military-like precision for thirty yards down the concourse. I had known Aboriginal Australians personally, even some of the more politically inclined, but these men and women were nothing like them. There was an intensity, a ferocity about them that made me shudder. They stood poised, looking straight ahead, unblinking, feet astride and arms by their sides. I had read about the civil rights movement, I had reviewed The Autobiography of Malcolm X for a national journal, and I seen television programs about “black is beautiful.” But this was something totally different. This was real, here and now. This was the country in which I’d come to spend my next six months. For a brief moment, I thought seriously of trying to escape from this bizarre cameo and jump back on the next flight to Sydney. As fleetingly as the thought came to me, it departed again. At the end of this elaborate guard of honor, I came face to face with a frenzied mob of television cameramen, newspaper reporters and radio broadcasters with microphones gripped in their hands. I felt like being in a dream in which I was wandering around on a film set where I had no right to be. What added to this sense of unreality was the presence of large numbers of police trying strenuously to keep the surging crowd of onlookers at bay. But these weren’t like police I knew. They carried guns, just like in the movies. In Australia in those innocent days, policemen didn’t carry firearms, which only confirmed for me that I had definitely arrived in America. But why all this hoopla? Was this how all overseas flights to the US were met? As much I liked to think my telegram had had an effect, this was a little more than I had bargained for. The precious telegram had indeed made it to my colleagues in San Francisco, who duly dispatched one of their number to come and collect me from the airport during my short sojourn. Jann McGuire was the lucky person to score this assignment. I had no idea what Jann looked like and she had no idea about me. Given the mayhem at the airport, it was little wonder she didn’t throw up her hands in despair and go straight back home. But not Jann. Even now, thirty-five years later, she remembers that Friday night in October 1971 as clearly as I do. “It so happened that Huey Newton was also arriving at San Francisco International Airport that night from his trip to China. The entire Black Panther Party was at the airport to meet Huey, marching in formation in their black berets. Airport security was a little panicked, and sent John's Qantas plane to an obscure runway and gate, and since I didn’t know him, I had a hard time connecting with him. I can remember walking up to many people when I finally found where the passengers had come in from his plane, yelling, ‘Mr. Burbidge?’” Alas, I never heard Jann’s desperate calls of my name in the midst of all the hubbub. I tried frantically to scan the crowd for someone who appeared to be looking for me, but nothing registered. Meanwhile, the Qantas crew was determined to get us all out of this frenzy and into an awaiting bus before anything happened to their charges. I made one effort to try and convince the flight attendant I was being met and needed to leave the group, but she wouldn’t hear of it. Once aboard the bus, we were whisked out of the airport and half an hour later, found ourselves in a small hotel where we were to be kept hostage until our return to the airport and the continuing flight to New York. But first off, we were herded into the downstairs restaurant for yet another meal. Given the gastronomic onslaught I’d been subjected to on the flights across the Pacific, the last thing I needed was more food. However, passing up “free” anything was against my most basic principles, so I sat down at a table with another passenger and proceeded to order. Just as I was getting stuck into my seafood cocktail, a young woman entered the restaurant. She stood for a moment and surveyed the crowd, as if she were looking for someone, before buttonholing a passing waiter, who then turned and announced to entire room, “Is there a Mr. Burbridge here?” Forgiving the waiter’s mispronunciation of my name, I dropped my spoon and raised my right hand, waving at the newcomer like a long-lost cousin. She came straight over to my table and introduced herself. As I recall the moment, I think of the movie title An Angel At My Table. Jann had just appeared from nowhere and I’d swear she had wings. We exchanged a few pleasantries and she recounted the events of the last couple of hours as she had searched in vain for me in the midst of wild mêlée at the airport. When that had failed, she persisted with the Qantas staff until she found out where they had taken us and drove straight to the hotel. I was impressed. This woman didn’t give up easily. But time was short. Would I like to go and see the Institute’s residence-cum-office? It was a Friday night and some of the staff were away teaching weekend courses, but I’d get to meet others. I was delighted to accept her offer. In spite of my weariness, I didn’t feel like sleeping. I suddenly felt I’d been given a new lease on life and was not about to let it pass me by. I excused myself from my fellow passenger and made a rapid exit from the restaurant. I couldn’t see any Qantas staff at the time but told my traveling companion that I’d see her back at the airport in a few hours. Little did I realize that my absence would cause a minor catastrophe among the airline staff. When they came to rounding up the New York-bound passengers and herding them back on to the bus for the return trip to the airport, they were one short. A quick scanning of the passenger manifesto revealed that I was culprit. My fellow passenger hadn’t bothered to convey that I had left with a friend, so the crew were beside themselves. Who was this Burbidge who had absconded into the wilds of a San Francisco night? What was he up to and who did he think he was, gallivanting off without our permission? While the Qantas office in San Francisco was in turmoil and about to send out a missing persons alert, I was merrily enjoying my first tour of an American city, in the company of my good friend Jann. I don’t recall much of those few hours on the ground, but I do remember the reception I received as I showed up at the Qantas check-in counter at the airport. “Where the hell do you think you’ve been young man?” was her opening line, as an irate ticketing agent stared me in the face. It was not only the words that fumed out of her mouth that shocked me but the look in her eyes that she was about to devour me on the spot. I didn’t have a chance to respond before she jumped in and continued. “We’ve been looking all over for you. We were about to call the police. You just disappeared from the restaurant without telling our any of our staff!” I felt like the errant schoolboy who had just broken the most hallowed school rule. It was all I could do to make brief eye contact, but somehow I managed to muster a reply. “A friend came to meet me and take me out,” I mumbled apologetically. “I told another passenger at the restaurant but she must not have let the staff know.” “You had no right to just run off like that without our permission,” she snapped like an irate schoolmistress. Wracked with guilt, I uttered a mild “sorry” and took the ticket she thrust toward me with a sense of disgust. Between my encounter with the immigration officer in Honolulu, my reception at the hands of the Black Panther Party in San Francisco, and the dressing down by the Qantas ground staff, I was beginning to have second thoughts about my new adventure to the Land of the Free. I felt anything but free right now. But I still had to cross this vast continent and catch another plane back to Chicago, before I arrived at my destination. Little did I realize that the final leg of this event-filled journey would present challenges of a different kind. * * * Chicago. A mythical place in my imagination if ever there was one, probably due to watching too many late-night episodes of The Untouchables, as much as anything. There was also all the urban sociology I read as a university student, in which Chicago was heralded as the classic living laboratory of the modern city, with its towering downtown Loop, its ritzy North Shore, and its endless suburbs fanning out from Lake Michigan in almost perfect concentric circles, not too mention its highly distinctive ethnic enclaves.. But more than anything, the story of Fifth City, the Institute’s landmark “community reformulation” project on the city’s demoralized and destitute Westside, had implanted itself in my mind as a beacon of hope for communities everywhere and drew me to it like a giant magnet. This grassroots effort to change the fortunes of the deracinated black population who lived in a twenty-block area was unlike most other attempts at urban renewal in the 1960s, which simply replaced horizontal slums with vertical ones. Spearheaded by a core of Institute staff who lived in an abandoned seminary in the midst of the ghetto, the project focused on transforming the imagination of the local residents, to help free them from being hapless victims of uncontrollable forces to masters of their own destiny. This was done in a thousand and one ways—creating a community-run preschool in which local women were trained to become teachers, beginning a slew of small businesses such as a laundromat and grocery store, opening a locally-run health clinic, securing funding to remodel derelict housing, and much more. The premise was: If you could do it here, you could it anywhere. Anywhere included Aboriginal communities in Australia that were crying out for clues about how they might begin to rebuild themselves—a major concern of mine throughout my students years and beyond. Getting to Chicago was no problem. After I said good-bye to my beloved Qantas crew in New York and found the American Airlines plane to Chicago, it seemed it would be downhill all the way. The only thing I remember of that last leg in my marathon trek from Perth was the artificial creamer served with coffee. I had never encountered it before and I after I tasted it, I hoped I never would again. I still have a hard time with it. America has devised some amazing inventions, but in my book coffee creamer is not one of them. However, that was a minor irritation compared to the competing sense of fear and fascination that gripped me as we drew closer to Chicago. When the captain announced we had begun our descent, I tried to prepare myself mentally for my entry into this strange other world that would be my home for at least the next six months. Till now, I could escape into the unreal atmosphere of airplane travel, jetsetting from city to city, soaring over oceans, eating, drinking and sleeping as if they would go on forever. But now this fantasy was about to end. There was no turning back. A sharp pang of terror shot threw my body. As our Boeing-707 prepared to land, I screwed my neck and peered out the window to take my first look at what I later learned was called Chicagoland. Gigantic tank stands that poked up all over the pancake-flat landscape were my first image on this massive metropolis. As the plane slowly turned in a 180-degree arc I glimpsed in the distance the soaring towers of downtown Chicago, thrusting up proudly to assert their dominance over all else. As we grew closer to the ground, I noticed the trees had no leaves. Everything had a bare, barren look, as if someone had taken a giant vacuum cleaner and sucked up every last bit of foliage. It was then I realized I was seeing my first real fall landscape. We had a season called autumn on the west coast of Australia, but since most of the native trees were evergreens, only a few imported varieties shed their leaves. The harsh world that presented itself to me through my window did little to calm my rising sense of anxiety as the plane touched down with a sharp thud on the runway. My first thought on arrival at O’Hare International Airport was for my luggage. The last time I had seen my brown Globalite case was when we went through customs in Honolulu, which now seemed light years ago. Would it make it through San Francisco and New York to Chicago? In all the traveling I have done since, I have never ceased to be amazed that my luggage has made it to its correct destination. Only twice has it failed to accompany me, and each time I have retrieved it within a day or so. But on this bleak October Saturday in Chicago, I was expecting the worst. My failure-syndrome machine was in full operation as I stood by the carousel, watching case after case go by without seeing mine appear. Finally, just as I was about to burst into tears, out it slid through the rubber slats. I was so relieved I nearly clapped for joy. The second-last leg of my journey was a bus trip from the airport to downtown. I had been instructed to go to the Palmer House hotel, from where I should take a taxi to the Institute’s campus on the Westside. I found the bus easily enough but was aghast how many of my precious dollars I had to spend on the ride. I remember nothing of that journey, since most of it was on freeways until we approached the Loop. But it wasn’t the road system that caused my memory lapse. I was engrossed in a mind game with myself, wondering how I would survive the next hour or so, before I finally came face to face with my future life. As the bus pulled up at the stately Palmer House, I stood in awe at its commanding façade and shining brass entryway. When the doorman offered to carry my case inside, I politely declined and indicated I needed a taxi instead. Several taxis were lined up outside the hotel, so I went to the head of the queue. The young driver jumped out to greet me and asked my destination. I had seen this address on brochures and written letters to it so many times that it was etched in my memory. “3444 West Congress Parkway,” I announced proudly. The driver screwed up his eyes and gave me a weird look. “You sure you have that right, buddy?” he asked. “Oh yes,” I replied. “It’s the Ecumenical Institute,” as though that should have removed any doubt. “Economical Institute?” he queried. “Never heard of it.” Not be outdone, I pulled out the invitation letter I had been sent by the Institute, which I had left on the plane in Honolulu. The driver stared at it as though it were written in Chinese. “Sorry, don’t know it,” he said. “Try the next guy.” I picked up my case and trudged to the next cab. The driver was African American. This should do the trick, I thought. After all, the part of the Westside I wanted to go to was about 99.9% black, since its former white population had fled to the outer suburbs. This driver was about twice the size of the first and half as enthusiastic in welcoming my business. He didn’t bother to get out of the cab but just lent over to the passenger side, chewing gum like a cow munching its cud. “Where yu headin?” he asked. “The Westside. 3444 West Congress Parkway. Between the Kedzie and Homan exits.” I was sure the extra detail would seal the deal. At least, it would show that I knew what I was talking about. Instead, it had the opposite effect. “Are you crazy?” he asked as he rolled his eyes skyward. “You’d never get me to go there if you paid three times the fare!” I couldn’t believe it. I’d come more than half way round the world, I’d finally got within sneezing distance of my destination, and I couldn’t get a black taxi driver to take me to the black ghetto! Maybe this Fifth City was not all it had been made out to be. Was I out of my mind to even try going there? Was it really too late to turn back? Persistence had always been one of my stronger traits and right now it came into play as never before. Once again, I picked up my case and headed down the line of taxis, telling myself to believe in the old maxim—third time lucky. As I did, a doorman from the hotel, who had witnessed my marked lack of success in getting a cab, came striding over. “Can I help you, sir?” he asked politely. “I hope to god you can,” I replied more curtly than I had intended. “I’ve just come all the way from Australia and I’m trying to get to this address,” I said as I thrust the invitation letter under his nose. “But these guys say they don’t know it or won’t go there.” As he glanced at the address, a wrinkled frown came over his forehead. “Well, I can see why you might be having a little problem,” he said. “This ain’t the nicest part of town. But let me see what I can do.” Waving me to follow, he went to the third cab in line and straight to the driver’s window. This driver was black, but seemingly younger and considerably lighter weight than the first guy I had encountered. After a brief confab with the doorman, the driver opened his door and made for the rear of the car. I walked towards him and without saying a word, offered him my case, which he dumped unceremoniously in the trunk. “Hop in,” he yelled. I barely had time to thank the doorman for his assistance. If I had been more familiar with American customs and had a little more cash, I would have tipped the doorman, but being “fresh off the boat” I was clinging firmly to my Australian manners in which tipping was not kosher. However, another part of my Australian heritage I quickly relinquished. Instead of jumping in the front seat and chatting with the driver, I slid into the back and held my breath. I had begun to feel distinctly uneasy about this whole enterprise, and sensed that keeping a little distance might be a smart move. The car sped away from sidewalk and into thick downtown traffic. Within minutes, we were racing down an on-ramp to the Eisenhower Expressway and heading west, for my first experience of freeway travel by car. In those days, there were no freeways in Australia. A four-lane road was about as serious as it got. Several things immediately struck me—the sheer number of cars on the road, their excessive length and width, and the wild speed at which they tore past. It was like being in a gigantic game of bumper cars that were hurtling out of control. I expected them to crash at any moment. It was exhilarating but terrifying. I clung on for dear life and tried to take it all in. The freeway was lower than the surrounding neighborhoods, so I had to look up to see the passing view. For the most part, it was endless rows of three-story tenement houses, all the same drab gray wood constructions. The distinct absence of color only added to my deepening sense of depression. As the minutes ticked by, we kept zipping past exits, whose names I noted on the green overhead signs. Suddenly, I saw Kedzie and looked at the driver to see if he seemed to be aware of it. Nothing indicated he was. Kedzie came and went and I began to feel nervous. Did he know where he was going? Was he taking me on a joy ride just to extend the fare? Assuming he knew more about where we were than I did, I decided to reserve my judgment for the time being. Then I noticed the first advance warning signs for the Homan exit. After a minute or two, the driver changed lanes, edging over to the right to make a smooth transition to the off-ramp. With a gentle swerve, he pulled off the freeway and up the ramp, decelerating to a less excruciating speed. For the next five minutes, we cruised around the neighborhood, both of us peering out the window for numbers that might give us a clue how close we were to our destination. Few people were on the streets, which was hardly surprising given the low temperature on this cold October day. Boarded-up buildings and empty lots strewn with old washing machines and abandoned cars told me I was probably in the right area. “What’s the name of this place you’re lookin for?” asked the driver, without turning his head. “It’s the Ecu-men-ical Institute,” I replied, as if I were giving elocution lessons. “Wazzat? Some kind of school or what?” he barked. “Yeah, like a college,” I replied, having no idea what the Institute campus looked like at all. Suddenly, he edged over to the sidewalk and pulled up beside three young black men who eyed our cab suspiciously. “You know some Institute around here?” the driver snapped. The older-looking one among them stepped forward as the group’s spokesman. “Yeah.” “Yeah, what?” said the driver impatiently. “Two blocks down and hang a left.” Without bothering to thank his informants for their critical information, the driver sped off and within minutes we were alongside an imposing stone building set in the midst of a vast quadrangle, surrounded by a high fence and with a church spire in the background. I scanned the building for an entrance, but nothing stood out. Then I spotted a doorway with an armed guard outside. That’s got to be it, I thought. “Stop here,” I instructed the driver. As the car slid over to the kerb, the guard ambled towards us. I looked at the meter and gulped. My American dollars were rapidly disappearing. I counted out the amount on the meter and put it in my pocket. The driver went to the trunk and hauled out my case. I handed him the money. He checked each bill and scowled. “No tip?” he asked. “Sorry mate, that’s all I’ve got,” I pretended in my best Australian accent. The security guard didn’t seem too impressed with my generosity either, but he let it pass. “You lookin for the Ecoomenical Institoot?” he queried. “Yes, I am,” I replied, relieved that at last I had found someone who knew what I was talking about. He pointed to the door. As he did, I noticed a highly tarnished brass plaque that from the road was all but invisible. So this was the grand establishment, I thought to myself. As nondescript as you would expect such a nondescript organization to be. I took a deep breath and rallied myself one last time. When I reached the door, I gave it a sharp rap. No response. I tried again and looked at the guard. “Sometimes it takes a few minutes if the person on dooty isn’t there,” he remarked. Consoled, I waited a little and knocked a third time. The door opened and a tall young man with a balding head appeared, walkie-talkie in his left hand. “Hi, I said. I’m John Burbidge. I’ve just come from Australia. I’m here for the Global Academy.” “C-c-c-c-ome inside. I’m H-H-H-H-Henry S-S-S-S-Seale,” he stuttered, as he held out his right hand to greet me. Henry’s speech impediment seemed much worse than mine, which I managed to conceal from most people most of the time. In a strange way, it was reassuring to find another person in the Institute who shared my little secret. But what were the odds, I wondered, out of the hundreds of staff in the organization that the first person I should meet on arrival was someone who also stuttered. Henry would probably never have guessed how strangely comforting this was to me. Before I had even crossed the threshold, I began to feel at home, shedding some of the many phobias I had accumulated since I began my journey four days before. I was exhausted and ready to collapse. But I had made it, all the way from Perth, even though I was a week late for the start of the program. Congratulations were definitely in order. Welcome to the United States of America, I said silently to myself. —John Burbidge -- GordonHarper - 06 Jul 2006

| I | Attachment | Action | Size | Date | Who | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

JB_Visa.jpg | manage | 46 K | 06 Jul 2006 - 20:04 | GordonHarper | Visa With Chops |

| |

Young_John_Burbidge.jpg | manage | 45 K | 06 Jul 2006 - 19:57 | GordonHarper | The Author At the Time of This Story |

Edit | Attach | Print version | History: r2 < r1 | Backlinks | View wiki text | Edit wiki text | More topic actions

Topic revision: r1 - 06 Jul 2006, GordonHarper

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback